TEMPE — When fans attend an Arizona State women’s soccer game in Tempe there’s a lot they’ll see and notice. They’ll notice the new large Big-12 branding adorning the field, a nod to the school’s new conference. They’ll notice the play of the 30-plus players between both sides that will feature in the high-level college game they’ve come to see. If those fans are particularly observant they’ll even notice the often very animated figure of ASU head coach Graham Winkworth patrolling the sidelines willing his team to execute his vision of victory.

Little to no fans – even the most observant – will notice two males sitting at a small table behind the ASU bench. One will be meticulously studying and charting from the computer in front of him while the other will be readying advice to be given to the players come halftime.

However, these tasks are only just a glimpse into the often thankless behind-the-scenes work of the male practice players who are over 5,820 miles away from home and dedicate hours to the Sun Devil Soccer Program. They’re not paid. They don’t get to play.

They just love the game.

“They’re teammates,” Graham said. “For me, they give up as much as the girls do from a working standpoint, from an effort standpoint, from a time commitment, but they do it knowing they’re not gonna get the reward on a Friday night and play in the games. They’re doing it selflessly completely.”

Shinnosuke Mima, 23, and Kento Toda, 25, are two large aspects of the team who do not receive much credit for the work they do. Both players moved to the United States from Japan where they both grew up as soccer players. Now they help the women’s ASU soccer team, by participating in practice with them, amidst a host of other tasks.

Mima was born and raised in Osaka, Japan where he lived for 18 years. He was always told by his parents to focus on his studies and was not allowed to play sports for a while growing up. Studies were the main priority of his family but eventually, they conceded, allowing Mima to follow his family heritage.

“At first my parents wanted me to study a lot,” Mima said. “Not playing any sports just prioritizing studying first, but one time they came to my school and looked at me and saw me sleeping the whole day and gave up on me studying, so they let me play soccer because my father played soccer.”

The unity soccer brings to life is what attracted Mima to the sport.

“I like the teamwork,” Mima said. “When we play soccer we sometimes fight with each other or something happens within the team, but when we overcome the suffering we become happy, and after we can have a conversation about it and laugh.”

After Mima graduated high school, he spent much of his college years in Florida where he did not play soccer at all. Ultimately, in 2022, he transferred to ASU and joined its men’s club soccer team that same fall.

Mima and Toda leaned on each other throughout their time with the ASU men’s club. Prior to them, there was not a single Japanese player on the team, which caused a challenge mostly for Mima who joined the team a year before Toda.

“In soccer, the first couple days or weeks I felt like no one really wanted to pass to me,” Mima said. “I don’t know if it was because I was bad, Japanese, or Asian. They didn’t want to pass so I had to get the ball by myself and do everything by myself the first couple weeks. That was a struggle for me playing soccer, and getting involved with the soccer players.“

Similar to Mima, Toda was born in Toyota, Japan, and also lived there for the first 18 years of his life. He played soccer for as long as he could walk and eventually joined one of the top-rated youth teams in Japan, hoping to become a professional.

“I played soccer all the time,” Toda said, “I didn’t hang out with my friends too much, I just focused on soccer practice and tried to become a professional soccer player.”

While becoming a professional soccer player was Toda’s goal, fate had a different plan for him. After failing the entrance exam to the University in Japan, he left the only home he’s ever known to travel just under 4,900 miles to Seattle, Washington. He left behind friends and family and most importantly the game he loved. Soccer would be an afterthought in his life for nearly four years.

After graduating from EF Seattle – a study abroad program for Japanese students – Toda came to the desert to attend ASU as a graduate student where he met Mima on the men’s club soccer team. The bond between two foreign players from the same country was struck quickly.

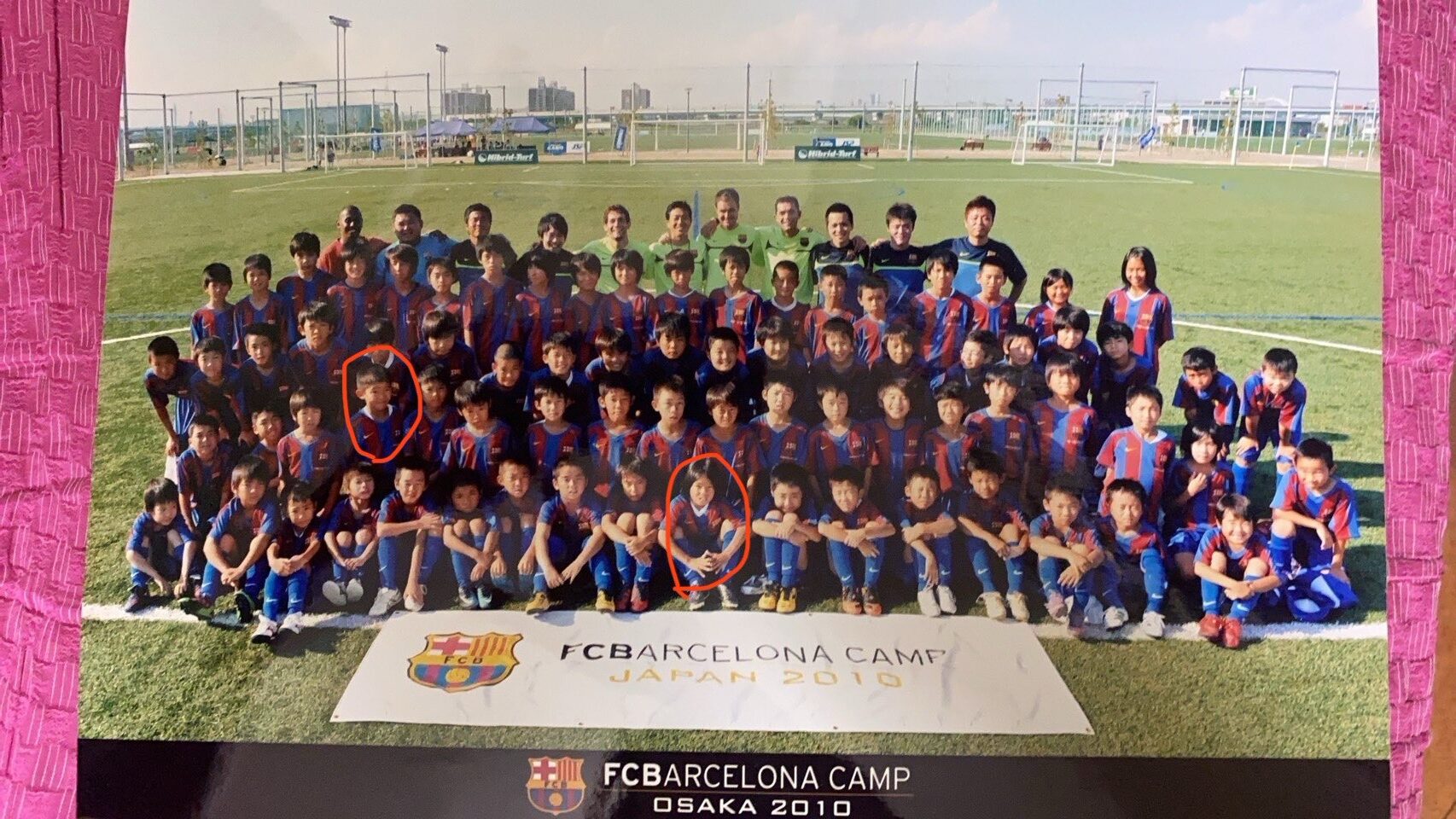

Amazingly enough unbeknownst to them at the time, this wasn’t the first time they had crossed paths in their lifetimes. FC Barcelona out of Spain is a pillar of European Football. The club’s youth outreach and international presence are monumental. They are one of the most followed and supported clubs in the world. They hold hundreds of youth camps across the globe every single year as well as having youth residency programs and teams in many countries outside of Spain.

It was within one of these camps, amongst nearly a hundred other youth players from Japan, that the two young soccer players met for the first time. While they are near inseparable now, a photograph is the only thing reminding them of their first meeting all those years prior in a country thousands of miles away from their next meeting.

“I didn’t know he was there,” Toda said. “I got a flashback when I heard his family name because he [Mima] doesn’t have a common family name. I then looked back at my photos and he was there.”

Nearly a decade removed from that camp, it was as if by fate the two soccer enthusiasts would meet again, both at their second state of residence in America. Both simply looking for ways to stay involved with the sport they love.

Mima and Toda had their worries about moving to the U.S. including safety concerns and issues with the language barrier. While both Mima and Toda learned English in Japan, they were never fully taught how to speak the language properly. Reading and writing came easy, but speaking was one of Toda’s main concerns.

“We could read English but we could not speak English, and that was the part that I was worried about the most at first,” Toda said.

Mima, while the language barrier was difficult, was concerned about his safety and well-being in the States. The difference in the environment sparked concerns about how safe it would actually be to live in the U.S. for Mima.

“I think how dangerous it is here and the safety,” Mima said. “In Japan, it is safer and we don’t have guns or knives and five-year-old children can walk alone but here they can’t. We have to take care of them more.”

The cultural diversity in both countries allowed for both of them to not have any surprises when moving.

“I would say there aren’t that many differences,” Toda said. “The culture is different, that’s true but we are diverse. The first thing I did was try to understand how (Americans) live and fit in, but I didn’t really feel any big or huge differences between (America) and Japan.”

Having Mima, a fellow Japanese native, already entrenched in the Arizona State soccer ecosystem helped.

“We have been building a good friendship so far,” Toda said. “[Mima] invited me to come and join in on practice together.”

For Winkworth, the work ethic and friendship these two created within themselves is just what the team needed. Winkworth determined that there were a few missing factors in his program and the infectious admiration the two international players had for the sport was one of those factors.

“They are all obsessed with soccer, they love soccer, and that mentality I wanted to bring to the team,” Winkworth said. “On the field, athletically, they are quick and technically very good as well and they raise the level of practice. Rather than having our 33rd, 34th, or 35th best players try to raise the level of our best players, we bring guys in who are potentially better than our best players and therefore raise the level of our stronger players.”

So in spring 2023, the staff reached out to the club soccer team and a few boys decided to join. Only three stayed. Mima, Toda, and another, Waleed Alshurei. Integrating them with the team was no struggle at all.

“It was seamless, I only had a couple of rules and they’ve been great with them,” Winkworth said.

Mima and Toda have developed larger roles than just practice players since joining. Their tasks now include studying film on their own time to give pointers during practice or so to mimic future opposing players in practice, setting up and taking down equipment, and recording the data analytics of games and stamina prior to and during games. They both dedicate a lot of their free time and effort to helping the team prepare for their matchups every week, while not being paid.

Simply for the love of the game.

“They really care for their teammates because they are a part of our team, they’re not just practice players they are a part of our roster they just can’t play,” Winkworth said.

During practice throughout the week, the duo’s main goal is simple. Find a way to make the team better. This includes Mima and Toda preparing themselves physically to try to emulate the players their team is playing against that week. Their daily schedules are similar: wake up, eat breakfast, go to practice, go to their classes, then work out and go home.

“My mission is to be more adjustable to how they want to play because every week it is going to be different because we have a different game,” Toda said.

They also serve as leaders from the sideline for the Sun Devils.

“They are really big communicators,” senior defender Lauren Kirberg said. “Something that we really have to focus on as a team and get better with is communication, but when they’re on the field they help us communicate and it gravitates everybody because I think everyone starts to pick it up.”

The two being on the sideline for the Sun Devils during games has been a big aspect for the girls in their improvement. Their years of experience and willingness to impart knowledge and general support from the sidelines are infectious to the girl’s level of play.

“They’re hard workers and really good role models to encourage the team every time that we’re practicing and playing,” junior defender Meighan Farrell said. ”Having them on the sidelines now with us during games is a big difference now cause they help and I can hear them on the sideline like ‘Go Mei go Mei’ and it’s awesome.”

ASU assistant coach Ross Alexander has seen them as emotional mediators as well.

“They bring a real feel-good factor to the team on game day,” Alexander said. “It’s an emotional game and they do a great job of understanding the emotions, when to celebrate when to be upset, when to be frustrated, when to stay away…I think it’s a very underestimated characteristic.”

The two who have made the cross-globe journey to ASU have become more than just practice players or pseudo-analysts for the team. They’ve become family. They’ve built amazing relationships with both the coaches and players.

Every team that competes in the NCAA women’s soccer postseason tournament receives medals for qualifying or being selected for the Big Dance. Following a disappointing 3-0 first-round exit to Santa Clara in 2023, the group made it a priority to bring back extra medals to hand to Toda and Mima. It was validation for the hours of work that did not go unnoticed and undervalued.

“It was great, I was really happy for them,” Kirberg said. “They helped us just as much as any other part of the team so I am really happy they got it.”

It was an emotional moment for Mima and Toda who were finally receiving affirmation for the labor they had given to the program.

“I was happy, at the time I felt like I was a part of the team so I was glad to get the medals,” MIma said.

It was true acceptance into the Sun Devil Family.

“It made me feel a lot more like I was a part of the team, not just a training partner,” Toda said.

The relationship between the two is unmatched and so too is their relationship with everyone on the team. They can be described as another part of the Sun Devil soccer family, being able to share memories and laughs every practice with the team.

“I call them my sisters,” Farrell said with a laugh.

2024 is a historic one for all Arizona State Athletics. It is the universities first Big 12 season across all sports. The two Japanese contributors have both dedicated large portions of their time to this team and have seen their work reflected in the team’s on-field play.

The pinnacle of the team’s appreciation for their hard work came on a senior night against cross-state rivals Arizona. Following ASU’s 1-0 loss to the Wildcats. Toda, along with fellow practice player Alshurei were honored along with six other seniors in the team’s ceremony.

“It’s all my pleasure,” Toda said. “It couldn’t be better than this.”

ASU will travel to Kansas City for its first crack at the Big 12 Tournament. The squad’s qualification for the conference postseason tournament was secured in large part because of all the work of the players, but also the innumerable and often unrecognized hours put in by the male practice players. They play, they crunch the numbers, they put away equipment, they coach, they do just about everything.

Fueled by their bond, originally fostered years before, in a country half across the world from the one they reside in now, they pass on their lifetime of experience with Soccer to a new generation of women at Arizona State.

A small amount of personnel can say they dedicate more hours to the success of the players than Mima and Toda and certainly not anybody who gets no external reward in terms of payment or playing time.

Their roles were never about, nor for, them. To play soccer every day is enough to satisfy the dreams of those young players in Japan with aspirations of playing forever. They simply wanted to aid the development of the players in any way they could.

They did just that.

“We are always happy to see the girls improving,” Toda said. “They improve every day, That’s always very exciting to see because some players ask how do I improve more and we answer and help them, then next week it happens quickly.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.